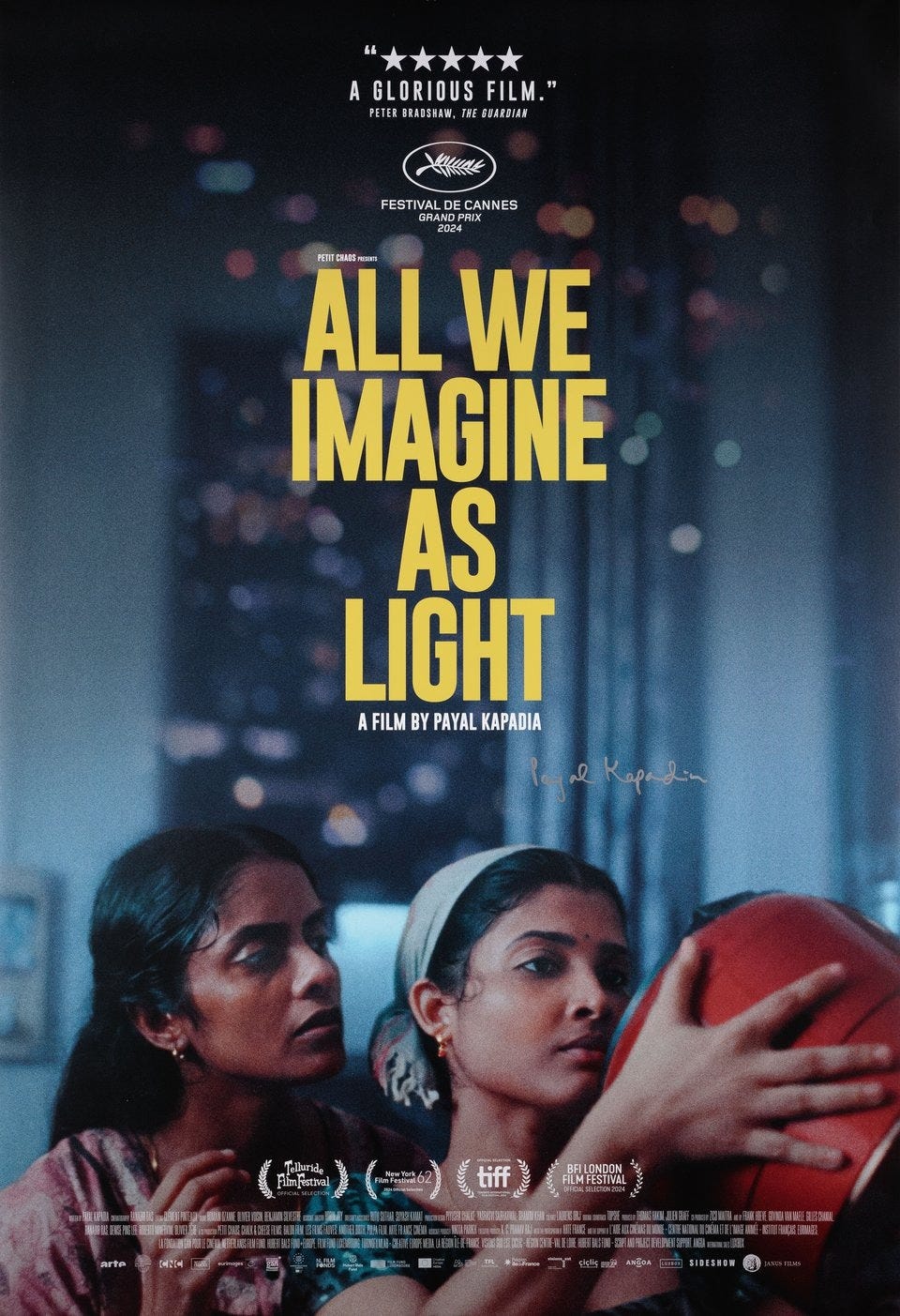

An Aesthetics of Tenderness

On Payal Kapadia’s All We Imagine as Light

In just two weeks, on January 18 and 25, I’m offering an online seminar on writing sex. Over two two-hour sessions (recorded for those who can’t attend synchronously), we’ll consider great sex writing by DH Lawrence, Philip Roth, James Baldwin, Miranda July, Raven Leilani, and others, and think about how they use sex to further character, conflict, them…