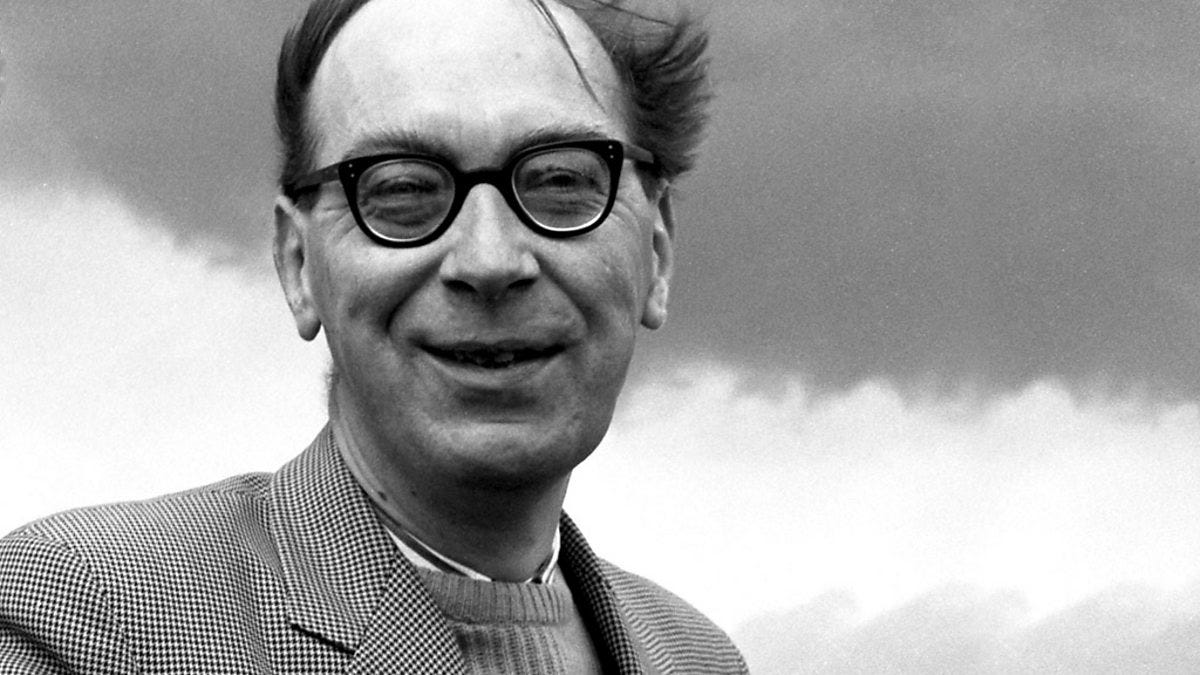

To keep myself from mindlessly picking up my phone when I need a break from writing, I try to always have a book of poems on my desk. For the past many months, that book has been Philip Larkin’s Complete Poems, the 2012 edition with the very useful notes in back. Larkin has long been a favorite poet, and for a while now I’ve wanted to do a deep dive—to read all his poems again, and also things I’ve never read, like his music criticism and his letters. I keep kicking that down the road, but the other day I visited a poem I hadn’t looked at on the page for a couple of years or so, though I think of it often—it’s a poem that often runs through my head when I’m trying to sleep. (I have a terrible time sleeping, and reciting poems to myself is the best remedy I’ve found; I recommend it.) It’s a poem I memorized by accident, kind of; I taught it so often it just stuck. I used to love teaching it, back in the days when I taught high schoolers; I think I used it for my first lesson every year I taught. It’s called “High Windows,” and it’s very famous; many of you have probably read it. In case you haven’t, it goes like this:

HIGH WINDOWS

When I see a couple of kids

And guess he’s fucking her and she’s

Taking pills or wearing a diaphragm,

I know this is paradiseEveryone old has dreamed of all their lives—

Bonds and gestures pushed to one side

Like an outdated combine harvester,

And everyone young going down the long slideTo happiness, endlessly. I wonder if

Anyone looked at me, forty years back,

And thought, That’ll be the life;

No God any more, or sweating in the darkAbout hell and that, or having to hide

What you think of the priest. He

And his lot will all go down the long slide

Like free bloody birds. And immediatelyRather than words comes the thought of high windows:

The sun-comprehending glass,

And beyond it, the deep blue air, that shows

Nothing, and is nowhere, and is endless.

I liked starting with this poem because, for a lot of my students at least, it was surprising; it didn’t sound like they thought poetry should. And also because the first order of business, in any literature class, but maybe especially a high school literature class, is getting students to see a text not as some hermetically sealed sacred object delivered from on high, but as a field of choices, a series of words any of which might have been something else—and even tenth graders can see that Larkin’s first stanza here is full of choices. Interpreting a text then becomes telling a story about why certain choices were made instead of others. It was a fun little exercise, imagining with my students all the other ways Larkin might have gone, the words he could have used in place of “fucking”; and this led, in turn, some years, to surprise at the fact that so many of the words we have for sexual acts are taken from hardware (screw, hammer, drill, etc.), and to wondering about why so many of them figure sex as a singular active force acting on passive unconscious matter.