“Art Is Pressurized By Endings”

Paul Lisicky on choosing your mentors, pushing against cynicism, & finitude in art

Last chance to sign up for the May 4 online seminar on the practicalities of The Writer’s Life, which is (amazingly) just a week away. The priority deadline to send in your questions is Sunday, 4/27 (ie, just two days from now)—but you can still send in questions after that, and there will also be a live Q&A. The questions we’ve received already are pretty terrific, and a little surprising. I was expecting questions about how to find an agent, for instance (and we’ll definitely talk about that)—but we’ve also received questions about how to break up with an agent. Interesting! I will be surveying friends for the best advice. I hope you’ll join us. You can find full info and registration here.

I’m still a little in shock about the news that Small Rain won the 2025 PEN/Faulkner Award. This Monday, April 28, at 7pm ET, I’m going to be chatting with Deesha Philyaw—winner of the prize in 2021, and one of this year’s judges—about the award. The event is online; tickets are pay-what-you-can (including a free option). I’d love it if you would join us. Full info and tickets here.

Finally, thank you to everyone who came to the second To a Green Thought Book Club. What a joy to talk about Isabella Hammad’s Enter Ghost with you. The conversation was thrillingly good. I’m excited for our next meeting, which will be June 29 at 3pm ET. The book under discussion will be Han Kang’s We Do Not Part, translated by E. Yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris. Also, I think we’re going to start recording these conversations for those of you who can’t join synchronously; more details about how to access those recordings to come. The club is open to all Founding Members of this newsletter—to join or upgrade your subscription, just click on the Subscribe button below.

This is a free newsletter. If you’re able, please consider supporting my work by becoming a paid subscriber.

*

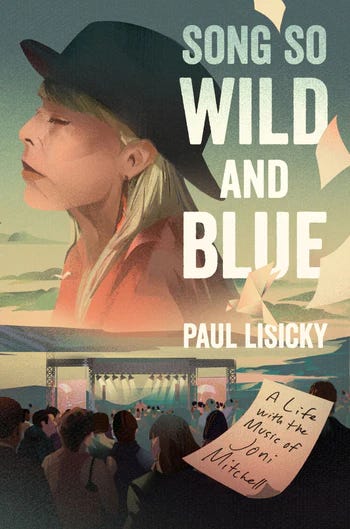

Earlier this week I had the great pleasure of chatting with Paul Lisicky about his new book, Song So Wild and Blue, at Prairie Lights here in Iowa City. Paul and I have known each other for a long time now—we’ve taught at writing conferences together, and even did a string of joint book events back in 2016. I love talking with friends about their work, and sometimes friendship allows for conversations that are a little more vulnerable and searching than maybe is the norm. I felt like that happened the other night. I’m very grateful to Paul for giving me permission to share the conversation here.

Song So Wild and Blue is about Paul’s lifelong love for the music of Joni Mitchell. It interweaves biography and reflections on Mitchell’s songs with scenes from Paul’s own life. At its heart the book is an account of aesthetic education: meditations on a series of encounters and relationships that have been crucial for Paul’s sense of artmaking—with Mitchell’s music as an overarching constant, steady but ever changing. Read on below for thoughts about writing intense moments, the joys and aesthetic challenges of new love, the vibe at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop back in the day, and more.

A Conversation with Paul Lisicky

Garth Greenwell

Paul, I’m so happy to see you. Welcome back to Iowa City.

Paul Lisicky

It’s been nine years.

GG

Luis and I were trying to remember whether you were here last in 2016 or 2020.

PL

It was 2016. My previous book came out in 2020—

GG

Oh, but Covid.

PL

That’s right. The book came out on March 17. There was a huge tour planned, I think you and I were supposed to do Mission Creek together. It was all canceled because of Covid. And you know, I was actually so excited about trying this new form called Zoom. It didn’t have any baggage then. I thought, Wow, 170 people have never come to one of my readings before, in the real world. And then you find out, after three or four events, that fewer and fewer people come. Because those 170 people are your core.

GG

Right, and they’re spread all over the country. Well, Paul, we’re your core. It’s wonderful to hear you read in real life. And you may not have been in Iowa City since 2016, but we did get to hang out this past summer, when we were on faculty together at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. You read from this book then. It hadn’t been published yet, so my first encounter with the book was hearing you read the very first pages.

For those of you who haven’t read it yet, the first section of the book tells how Paul met his partner, Jude. It’s unbelievably beautiful. You know, every year, I feel like there’s one passage in a book that I hold on to as the thing that makes me feel the most writerly jealousy. Last year it was an adjective in

’s novel, The Future Was Color. It’s so brilliant; I would kill to have written that adjective.PL

What was the adjective?

GG

Well, the context is a little dirty, it’s maybe not rated for this event. But you should all go read Patrick’s book. It would take something really spectacular in the second half of the year for my 2025 jealousy not to fixate on the last sentence of the first section of Song So Wild and Blue. I remember hearing you read it last summer, and feeling like my heart just flew out of my chest.

So it makes me really happy to get to talk with you tonight. I wanted to start by asking a big question about the structure of the book, which constantly surprised me. The writer

has called the book an anti-biography biography and an anti-memoir memoir. I’m fascinated by the way the book moves through time. It’s in three big sections: childhood and adolescence; then sort of coming of age as a literary person, including some time in Iowa City; and then later in life, including a transformational new love. But you don’t present a continuous narrative; instead there are a series of scenes—and not always what one might think of as the most dramatic or obviously key scenes from those stages of life.So I was wondering about scene selection. Did you know which moments were going to be part of the book, or did you discover that as you went along? And then when did you discover how the two big strands, Joni Mitchell and Paul, would interact?

PL

I wrote this book differently from anything I’ve ever written, in that I mapped out the structure beforehand. I never recommend that to my students. I think of it as a mortal sin.

GG

Why? Why is it a mortal sin?

PL

My own personal procedure has always involved accumulating a lot of pages and sort of finding the work after wandering for four or five years. But this time I wrote the map out from the get-go. Some things did change, of course. My relationship with a man named Jude was just starting when I began the book, and I thought, well, this is going to be a wonderful coda, maybe five pages. And then, as I wrote more and more of the book, I thought, well, this is a prologue. And then finally I decided, or it just seemed inevitable, that the opening section would be about Jude, because Jude led me back to Joni’s work.

You know, I loved Virginia Woolf when I was younger, and the idea of “pressure points” and “moments of being” has always infiltrated how I think. So I tried to identify multiple pressure points when I thought Joni’s work was teaching me something—not only how to be an artist, but how to live. Interestingly, having that map helped me—it helped me discover more on the sentence level.

That was an interesting paradox. To have such strong girders holding it up in my imagination allowed me to wander a little bit more. I think that accounts for some of the wandering, especially in the early chapters, where the speaker attempts to go into Joni’s head, or into Joni’s mother’s head. So, yeah, it was a new way to think. I’m not sure I’ll ever write that way again.

GG

Do you know why you tried that method this time?

PL

Oh, for a really practical, strategic reason.

GG

Were you on deadline?

PL

I was on deadline. I had never submitted a book that I didn’t write fully through first. I have a wonderful editor, who is a Joni fan, and he knew that I was a Joni fan, and he sent me a DM on Twitter and said, Paul, what would you think about writing a Joni Mitchell book? I immediately wrote back, saying that sounded interesting and cool. And then he said, Who’s your agent? And when I told him, he said, I’ll be in touch with him next week. So I had to present a convincing synopsis and map in order to sell the book.

And I just thought, oh my God, this is dealing with the devil. I mean in terms of my own old principles. I wanted to make sure that it became, for me, a work of integrity and work in which, you know, discovery activated everything.

GG

You mentioned how, early on in the book, you enter into Joni’s consciousness as she’s conceiving of songs in a kind of novelistic way, and then there’s a wonderful scene where you enter into Joni’s mother’s consciousness as she’s watching her daughter in concert at Carnegie Hall. I feel like that must have taken a lot of chutzpah.

So, two questions. First: was that hard? Did you feel a resistance to that, or did it just happen? And second, why does it fall away? Because in the later parts of the book, it doesn’t happen.

PL

That’s such a good point. I was not conscious of it falling away, but it felt like those iconic scenes needed to be available for the reader before the book, you know, took wing and became something else. Yeah. I was so scared that I just went forward and did it. You know, it’s like—

GG

Wait. You were so scared you just went forward and did it?

PL

You know, I just felt I could fuck this up at any moment, I could really ruin my life, my love for Joni. I could screw up this wonderful opportunity. It could just be horrible in so many ways. I think the horror of that just gave me permission.

GG

So this is really a very counterintuitive book. You know, you plan it in a way you never have, and that allows you freedom; and then you have this thing that’s really terrifying, and that allows you to be daring. I feel like there’s something I should learn from this.

PL

I mean, you probably understand what I was doing structurally better than I do now. But you know, as I was putting it together, I was very sure: this belongs here, and this belongs here, and this belongs here.

GG

This is a book about a lifelong relationship with an artist, and it’s a relationship that has ups and downs. It’s complicated in moments, and it involves judgment. You talk about moments in Joni Mitchell’s career when she seems to you not to be meeting the standards of her best work. There’s a wonderful line very early on, in the section about getting to know Jude, and getting to know him through Joni Mitchell’s music, in which you talk about your disappointment in some of the songs being “a deeper form of respect.”

I’m so interested in that. It’s something I think about in relation to certain authors, maybe especially James Baldwin, who I think and write about a lot. It seems to me that the sanctification of James Baldwin is fundamentally a way of not taking him seriously. Could you talk about the role of disappointment in this relationship that has been one of, as you say, mentorship for you, both as an artist and as a human being?

PL

It’s fascinating to me that I often spend more time listening to the songs that disappoint me, because I have a gut-level feeling that there’s something there that I haven’t been acute enough to access. I think it’s only recently that I’ve been able to hear the songs of the mid 80s, which I think are less songs in themselves than they are like sonic landscapes. They’re created in the studio. They’re really interested in layering, which I think has a thematic purpose. I don’t think that that layering is just, “I’m going to try a new sound”—I think it’s central to the vision of that work.

So, yeah, I think I have faith that there’s something to be discovered on the other side of disappointment. Joni never shrugs it off, she doesn’t call it in. I feel that in every song. I think that’s what I most love about her: I feel like every song is, on multiple levels, an act of discovery, and I might not have the ears to hear what she’s been up to in a particular song right away. There’s something thrilling about any piece of work that continues to teach you over time.

GG

By the time you encountered Joni Mitchell’s music, you were already a musician yourself. I think many readers may discover through this book that you have a background as a composer and published liturgical music as a young person. You’ve talked before about how your training as a musician informs your writing—you even talk about writing prose as being like writing a song. How is writing prose like writing a song?

PL

You know, my sentences have become much more sonically attuned in the last several books than in my earliest books. I think I was primarily interested in description as an activator when I first started writing, for years and years. Then I wrote a book which is kind of a one off. It’s essentially a fragment of a longer work that I never brought to publication, but writing it I learned something about cadence, about the sweep of individual sentences, about breath and pause. And at that point, I started to read my work aloud as I was writing it. So in some way, you know, even though they’re not conscious melodies—I’m not putting notes to those words—I’m thinking of those sentences as musical phrases.

GG

Is it all at the sentence level? Or is there any way that music also informs how you think about higher-level structure?

PL

There probably is, just if you just think of the pressure building, things like crescendo, a sweep toward a height and then a release. I mean, one wouldn’t want to keep repeating that, but that’s central to so much of the Western music we know, and I think it’s behind what I’m doing structurally as well. But I want to make sure that I’m not simply repeating that pattern because it’s a familiar and maybe pleasing effect.

GG

A lot of your education, maybe most of your education, as a musician was self-directed. You talk in the book about how important it was that there wasn’t a lot of pressure put on your music making when you were young, or a lot of expectations. Your education as a writer was a little different, and part of that education happened here. You’re a graduate of the Writers’ Workshop, and you write about that in the book. I wanted to ask if you would read a paragraph about the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. It’s on page 102.

PL

I have not reviewed this paragraph.

GG

You can say no! I don’t believe in coercion. But there’s a paragraph on page 102 that felt to me like it contained some big feelings. It starts at the very bottom of the page.

PL

Oh, gosh, you’re right.

As to what we were expected to value across the arts? Understatement. Control at all costs, even down to the level of the syllable. Nothing ornate or cadenced, too bright or too dark. High emotion, no. Was racism, misogyny, homophobia, classism twisted in its cloth? Likely. All of this was unsaid, of course. And if you crossed over an arbitrary line of expression, someone was always there to call you on it, which didn’t mean he didn’t want to cross over with you, because he knew that’s where the life was. That’s where growth and change were. But power didn’t live on that side. Big agents didn’t either. Contracts for first novels? No. So given the choice between life and death, some always chose death, with a knowing shake of a head and a rueful squint. They got to be in The New Yorker one day while you kept your beautiful life.

I actually didn’t mean that to be mean.

GG

I don’t think it’s mean! But I do think there are some feelings in it.

PL

There are feelings, yeah. Well, so you know, I followed my time at Iowa at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, which was fascinating, because I think what I learned here was an experience of socialization, not just the level of writing, but at the level of learning to talk to other writers, learning to talk to guests, and all of that. Then I went to Provincetown, and here I was with a lot of visual artists who would hear the work of esteemed younger writers, and say, That’s boring. It was really fascinating to be in two related experiences, where I got to think about values, about aesthetics, and about what that meant for my own work.

GG

In the paragraph right before the one I had you read, you talk about an encounter where you sensed a fellow student in the workshop looking at you askance for having shown too much enthusiasm about something.

PL

I was very excited to hear “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough”—Diana Ross’s version.

GG

That seems like an appropriate excitement!

PL

It was a different Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Everyone was white, practically, with a few exceptions. In all those people, I think there were three LGBTQ people. Many people had gone to very fancy schools. And so there were assumptions about what art should be, right? I’m positive it’s different now.

GG

It resonates with something you say later in the book about your family home, where you say, there too a certain kind of enthusiasm was tamped down. You say the only safe opinion to express was that you didn’t like something.

So I wanted to ask you, what is the role of enthusiasm, the role of love, in an aesthetic education?

PL

That’s a beautiful question. It’s a whole book. And I feel like enthusiasm, the expression, the conveyance of enthusiasm, is what this book wants to uphold. It’s pushing against the no of cynicism. That reflexive cynicism, a reflexive tamping down of feeling. Certainly all of those issues were coming up in my new romance. It was the first time I’d been with someone who seemed open in a way that no one else I’d ever met was open. Who’d been really loved by his parents, who’s still loved by his parents as part of their family.

I think that’s probably why some of these book events have made me feel—I mean, I’ve enjoyed every event, but some of these events have made me feel super skinless. I stagger home and think, That went really well. Why do I feel so weird? I think it probably has something to do with that, with putting oneself out there with one’s enthusiasm or love, without any protective coating.

GG

Well, we’re going for ramen after this, Paul, so you won’t be alone.

I guess this is another kind of big question. I’m interested in this book as fundamentally a book about aesthetic education—and also about, as you say, education in being a human being. I guess I think those things are a single education.

Joni’s early experience of polio, of very serious illness, being immobilized on a bed, runs throughout the whole book. You hear that experience again and again in the music that she makes across her life, in the songs you write about. It made me wonder, and I think the book wonders, about the relationship between vulnerability, debility, and art.

There’s a beautiful line in the book where you say, “How does a life force negotiate with limitation?” A lot of the book is about aging—your own aging, Joni’s aging, your parents’ aging and their deaths. It’s about finitude.

There are also very beautiful meditations on Joni’s recent concerts, where younger artists have surrounded her and enabled her to return to performing. You see in that an almost utopian counter-vision to the reality of how in America the elderly are discarded.

What is the relationship between art making and vulnerability, art making and debility, art making and mortality? At one point in this book you say that a scarier thing to come out about than your gayness as a young person would be your realization that all of us are going to die. Could you talk about that?

PL

Death is threaded through the book, the limitations of the body are threaded through the book from sentence one. And art is, in some way, in resistance to that limitation. Art is pressurized by endings. I’m a little stumped, because it’s a beautiful question and a beautiful thought, and I think it’s so close to me that I have a hard time talking about it directly without enacting it on the page.

GG

That’s fair. You did write the book

PL

I’ll be thinking about your question for days.

GG

This a book of encounters. It’s a book, as you said in your intro, about multiple mentors, not just Joni Mitchell. Some of them are not human mentors. And there are—

PL

You’re the first person who’s pointed that out.

GG

Oh, good. Good for me! [Laughter.] So there’s a beautiful encounter with an owl, very late in the book. And in the middle of the book, in what actually, in a way I can’t rationalize, feels to me like the heart of the book, there is a long encounter with a deer. You’re pressed for time in the scene, you have to catch the boat off the island, or something—

PL

Yeah, I was on Fire Island, and the last boat of the afternoon leaves at 4pm.

GG

And it’s devastating to walk away from this deer, with whom you’re sharing this intense moment of communication.

PL

We’re face to face. This big, big deer with a big rack of antlers. He comes over to me, and we just look at each other for five or ten minutes. I’m just talking to him. After a minute or so, he knows I’m not going to give him any food. But it’s this moment of mutuality, of just curiosity passed back and forth, and it felt like the most significant moment of my life.

GG

Can I quote what you say in the book? It’s a beautiful moment. You say, “I was failing him. I was failing the largest moment in my life.” Why was that the largest moment of your life? Why was this so devastating?

PL

Well, for one, I wasn’t able to give language to it, and by not giving language to it, I couldn’t control it, which was thrilling and devastating at the same time.

GG

So then, what was it like to write it?

PL

I was just super quiet, and I tried not to inflate it. I wanted to honor its significance, but I wanted to be as plain spoken and precise as possible, and do whatever I could to honor the duration of it in the structure of that passage.

GG

Beautiful. This is my last question, and then we’ll open things up for Q&A. In your first chapter, which we’ve already mentioned, you write about a new love that feels like a rebirth or a restarting of life. It comes into the book at the beginning and the end. You talk about how when you were first getting to know this guy, Jude, over the internet I think, you were clearly really into him, and maybe because of that, you were really tempted to shut everything down before it could get started.

That echoes something you’ve just said in the book about starting to play the piano and explore music. You talk about how, had your mother responded to you in a different way, it could have shut music down for you before it had gotten started. Those two passages, at the very beginning of the book, for me draw an equation between love and the creative act. And I wondered if you could talk about that, about relationships as acts of creation, and also about writing a book as an act of love.

PL

Yeah. I so much wanted to write something that captured the profundity of this connection. It’s the first time I think that I felt, like, love coming toward me and coming toward him. When we think of romance, we often think of an inequality that’s part of the map of it, that keeps the wheel of it spinning. And it didn’t feel like that. There was such a temptation to—well, I wasn’t going to run away. But after a life of relationships—lovely relationships, but many relationships that ended in such hurt and disappointment. After that I wanted to protect and honor this experience. I didn’t want to get it wrong.

It’s interesting. He really wanted me to write it, too. He coaxed me to write it.

GG

In fact, there’s a moment in the book where he says, Write this right now. Write what you just said to me. And you say, Do I have to, and he says, Yes!

PL

So I did not want to concretize that experience. I wanted it to have the fluidity and volatility of change and transformation. It felt there was a lot riding on writing that. It’s so funny. I was just talking to him before this reading. He said, What are you going to read tonight? And I said, I’m going to read the John Kelly / Joni section, and I knew he was disappointed that I wasn’t reading the opening. He’s the rare person who wants to be written about and read about.

GG

For those of you in the audience, at that Bread Loaf reading last summer, Jude was in the first row, and there was something kind of overwhelmingly powerful about hearing you read this and also experiencing him experiencing it. So I understand that he would want you to read that.

Q&A

Question 1

There’s a lot of great covers of Joni songs. And it’s interesting because she’s known for her lyrics and her great poetry and everything, but it’s amazing how well those songs can work without words, in jazz covers. I remember Fred Hersch, the jazz piano player, telling his students, You need to think about the words when you’re playing the song. And I just wonder if you had any thoughts about the phrasing and the lyricism, how the two are linked, being both a musician and a writer.

PL

Yeah, that’s a great question. She apparently writes the music first, before the lyrics. In many cases, they’re not linked. She refers to the lyrics as “parqueting” the melody. But I’m so glad to hear what you said about phrasing, because that’s something that I’ve learned a lot about, particularly from Jude, who’s also, among many things, a vocalist, and he’s taught me how to hear what she does with certain vowels. It feels like on every level she’s alchemizing visual art into sound. So when she’s singing about light on a bay, she’s wavering her voice, holding it so you see that picture. It makes sense that jazz musicians, instrumental jazz musicians, know what to do with the work. Because I think they know how to traffic in the visual, how to work in pictures.

Question 2

Thank you for your wonderful work. I’m a visual artist first and then a poet second, and I was wondering if there’s a movement in the literary world, in the same way as in the art world, where joy is becoming resistance and enthusiasm is a source of power.

PL

I think I wanted to do that as I was writing this book. Some of my previous books have been a little thornier, so here I wanted to think about how to write about joy and light in a way that doesn’t use borrowed language, in a way that doesn’t feel sentimental, but sort of strips away the protective coating. I started the book in 2021. I thought, this is going to come out in a really fraught moment. I wanted to write something that was true, but also felt nourishing and also said, in a sweet way, Fuck you to all of the powers that want to tamp us down. Tamp out the senses, the body, joy, community, togetherness, spontaneity.

Question 3

I really loved that moment when you talked about the deer and knowing that this was such an important part of your life, but then having to reconcile that with going to get the boat and come back to real life. I’m really curious about moments like that, when you have to reckon with important emotional moments and also the real world.

PL

Yeah, that’s exactly what was at stake. I mean, if I chose to stay in that circle, I would have had to spend the night there, and I had a place to be tomorrow. I must have been weighing those two possibilities, and I made the heartbreaking choice on some level. But that moment has continued to stay with me. I think about that moment every time I see another animal.

GG

I think the end of that section, the last line, is something like, “I was hurrying away from love, and I had done that before.”

PL

Yeah, I think I was probably anticipating heartbreak to come. That moment knew more than I did. That encounter knew more than I did. Our writing knows more than we do. Our senses know more than we do.

Question 4

Were you afraid of taking an artist that you love so much and then talking about it in a book? Or, you seem like very fearless artist, so maybe there’s no fear.

PL

Oh no, there’s fear. Fear and fearlessness are marbled and of a piece. But--

GG

Wait a minute, that’s a profound thing to say. “Fear and fearlessness are marbled and of a piece.”

PL

Yeah, it’s—I think what was tough about this book was, like, writing my jet fuel. You know, I know writers who will not touch their jet fuel. Like, that’s precious and sacred and meant to be protected. It’s meant to be kept close to the self. And I just decided that I wasn’t going to do that, and I hoped to write something that would help the reader get in touch with their jet fuel.

Not necessarily Joni Mitchell. I was aware that this book was going to be for Joni fans. But there are also going to be some people who might not know anything about music, and my hope was that, you know, Joni as avatar for me could help you find meaning with your own avatar.

Maybe you’re not a deep fan of Joni Mitchell’s music, but maybe you’re a fan of Miles Davis, or of a certain painter. I want the book to open up a possible engagement with the art that’s meant the most to you, to open up the beginning of an inquiry.

That sounds very fancy, but I do think our art saves us. It saves our lives in ways that you can see, and I think it’s especially important right now, for all the obvious reasons.

So grateful you took time to lovingly edit and post this! Thank you. And thanks to PL for his insight and the ableness to articulate it with such clarity.

Wonderful conversation. I love the exploration of enthusiasm as a value (for writers, for readers) — I feel it’s an especially important one now, in this grim time socially and politically.

And the question of touching or not touching one’s “jet fuel”—fascinating.