A quick note to start: Next month I’m going to be spending a couple of days each week at Vassar College, as their Writer in Residence this year. I’m looking forward to it! The residency kicks off with a reading on Wednesday, February 7th at 6pm. You can find full info about that here. If you’re in the area, please come say hello.

*

I get asked to talk about style quite a bit, and especially to talk about how one becomes a better stylist. Actually I don’t like the language of “better” when it comes to style, since it seems to suggest that there’s some goal-directed, teleological progress involved, some point of perfection towards which we strive. I don’t think that’s true. First of all, I don’t think there’s any evaluative comparison of different styles: any highly functioning style presumes its own standards of excellence, which are incommensurate with the standards of other styles. Setting Hemingway beside Henry James, or Elfriede Jelinek beside Ann Patchett, is an excellent way to think about the possibilities of style; trying to erect a hierarchy of value among them seems to me nonsensical.

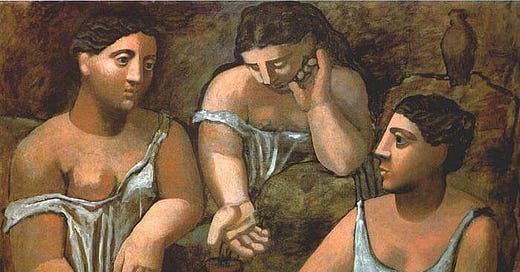

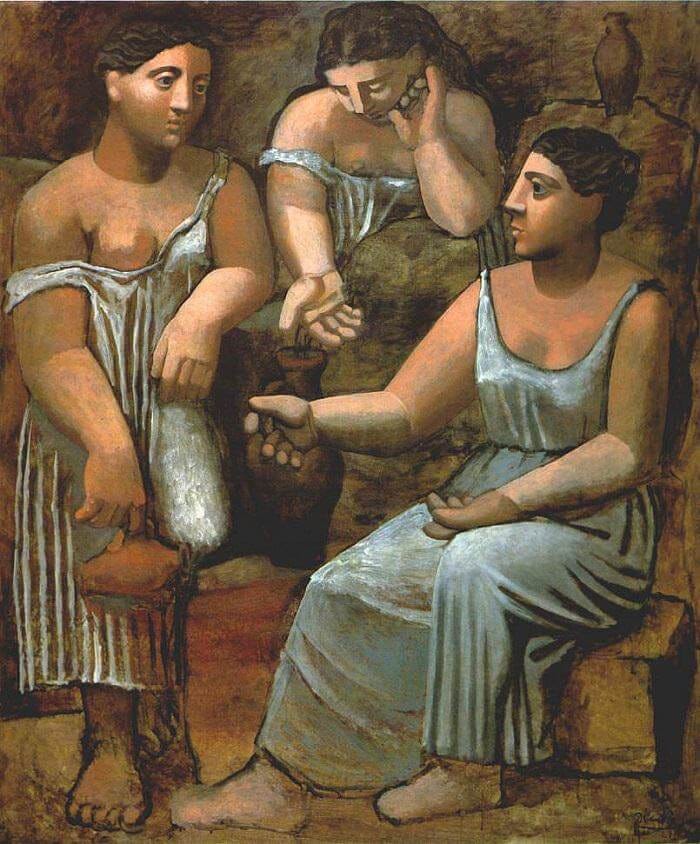

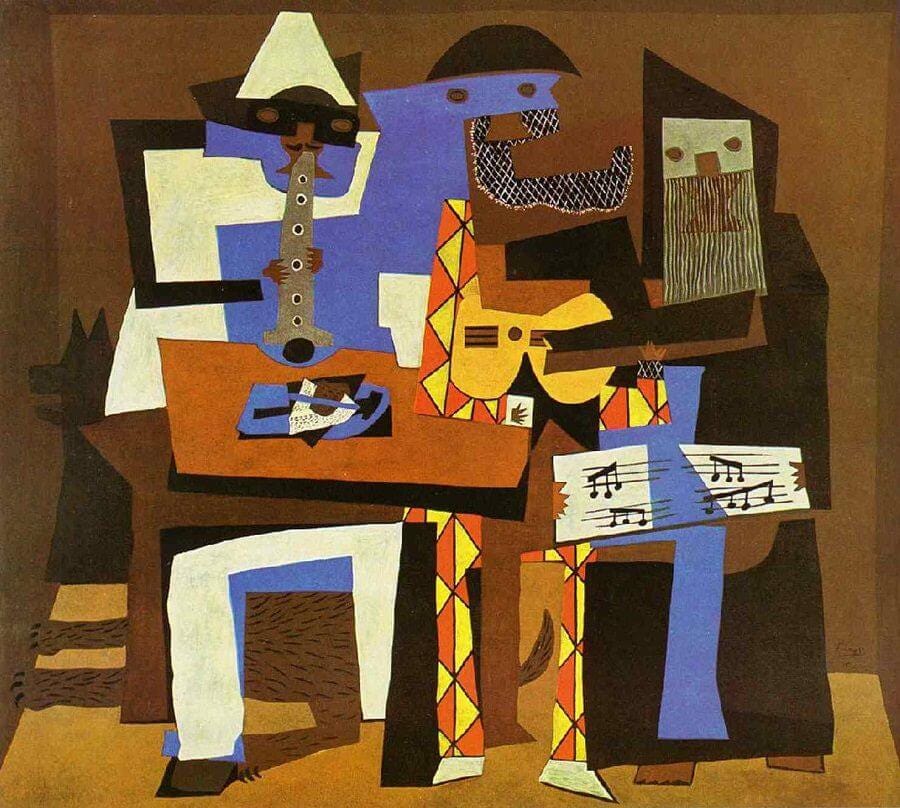

I like better to talk about “deepening” or “enriching” one’s style, though maybe I’m just deluding myself that those terms elude the trap of teleology: if a style can become “deeper,” does that suggest some final, ideal, deepest style? I’m not sure. And I don’t think there’s any language that can get us around the fact that there’s something deeply mysterious about style. Language of deepening or enrichment doesn’t capture the way an artist’s stylistic development (“development” too is a suspect term) can include radical breaks or heterogeneity. Luis and I just visited the wonderful Picasso in Fontainebleau exhibit at MOMA (it closes February 17th, catch it if you can), and it was amazing to see the way Picasso worked in neoclassical and Cubist idioms at the same time, in the same few weeks. A genuine mystery of style, the way that Picasso progressed by radical breaks, radical reinvention, radical assumption of new styles—and yet always, across his oeuvre, remains recognizably, ineluctably Picasso. I don’t think there’s any language, any neat set of concepts, that can account for that.

In any case, style is hard to talk about, hard even to define. But I think it’s worth trying. I remember feeling deeply frustrated, as a student, with conversations in workshop where style would be mentioned but always nebulously, vaguely, with words like “flowing” or “choppy” or “beautiful” thrown around—words that say something, I guess, but not very much. (This isn’t to mention workshops where style wasn’t talked about at all.) When I started teaching workshop myself, I wanted to be more concrete; I wanted to give students tools to turn their vague impressions of a writer’s style into analytical observations. This meant talking about diction and syntax and genre and tone, things that we can be precise about, and that can help writers see elements of their own style that otherwise remain opaque. And, once they can see them, they can think about manipulating them.