How to Take Notes (& Why)

On reading less efficiently (with process photos); unpacking a sentence by Henry James

The title of this post is a not-very subtle reference to the online class I’m teaching in January on the how and why of writing sex. Over two two-hour sessions, we’ll consider great sex writing by DH Lawrence, Philip Roth, James Baldwin, Miranda July, Raven Leilani, and others, and think about how they use sex to further character, conflict, theme. (An earlier iteration of this class was called “What Sex Can Do”; the answer turns out to be: pretty much everything.) I’d love to have you join us; full info and registration here.

Small Rain has continued to make its way onto end-of-year lists. I’m particularly happy that the New York Public Library chose it as one of the Top Ten Books of 2024; the Chicago Public Library also chose it as a best book of the year. The Washington Post selected it as a Notable Book, and it made NPR’s year-end list as well. If you haven’t picked up a copy yet, I hope you will; all the online links are here. I hear it makes a great holiday gift, too.

Speaking of gifts, did you know it’s possible to give someone a gift subscription to this newsletter? I’d be grateful if you’d consider it, and thank you for making it possible for me to write these nerdy little notes on culture. Here’s a button to make it easy:

*

Years ago, on one of the little coffins-with-wings that shuttle you from Cedar Rapids to whichever hub will send you where you actually want to go, the man sitting beside me asked me what I was doing. I was doing what generally I’m always doing when I travel: strenuously trying to seem the sort of person who isn’t spoken to on planes, and also marking up a book. But what are you marking it up for, he pursued, as I knew he would; the problem with talking to people on planes is that they don’t stop. He had never understood it, he said, back in high school and college when he had teachers who wanted him to mark up his books, he didn’t see the point. It just slowed you down.

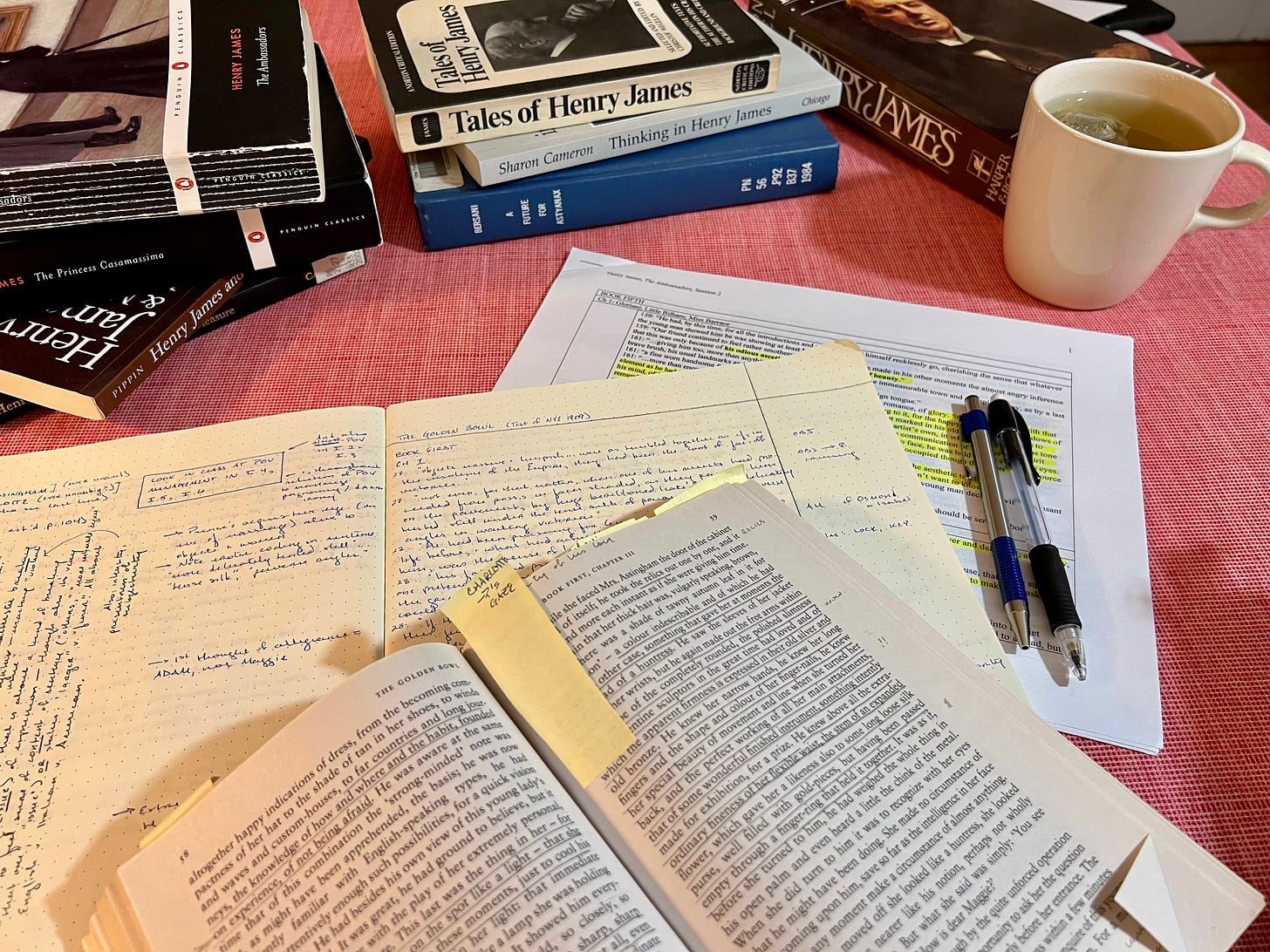

The easy, utilitarian answer to this is that annotation is a mnemonic: to review or recall a book, you can flip through and read the underlined bits instead of rereading the whole thing. What’s more, it’s not just the book you recall: it’s your experience of the book. A book you read multiple times becomes a time capsule, or a kind of diary, a document of your life. Anyone with a library knows the pleasure of this, and annotations increase that pleasure. I almost always have a pencil (always a pencil!) in hand even when reading for pleasure, not for teaching or writing; it’s a pleasure to pick up a book, years later, and see what lines I was struck by. (And also, since I’m that kind of person, finding receipts, ticket stubs, souvenirs of all kinds, stuck between the pages.) Finding a book in my library that’s utterly free of marks always makes me a little sad. It’s like a house somebody lived in without leaving a trace.

But memory is really the least of it. Marking up books doesn’t just make a record of an experience, it deepens the experience. When I was a high school teacher we talked a lot about “active reading”—about reading conceived not just as passive receipt of information, but as an encounter, a conversation. I remember feeling, early in my time as a teacher, that the key insight I wanted to convey to my students was that reading is creative; that a book isn’t some fixed, unchanging monument but instead a living thing, a field of activity, something to think with. Marking up a text is a record of that thinking, but again, it’s more than that: it’s the thinking itself. This thinking leads you deeper into the book, helps you see things you wouldn’t see without your annotations; but while your thoughts may start from a particular page, a particular sentence, from somebody else’s words, that’s not where they stop: the endpapers of my books are full of ideas for new stories and essays, lines for new poems.