This is the first in what I hope will be a new series of conversations with artists I admire, about their own work or something they love. Before I get to that, though, a couple of quick things. First, time is running out to register for the class I’m offering this summer, Saying Yes to Life, about what it means for art to be “affirming.” It starts this Saturday, July 8. (Sessions will be recorded, in case you have to miss one, and scholarships are available: the email for that is in the course description.) I wrote about the course and how it relates to things I’ve been thinking about in the last dispatch of this newsletter, so I won’t rehash it here. I hope you’ll join us.

Second, as I’ve mentioned a few times, there is a very beautiful new operatic adaptation of my first novel, What Belongs to You, by the composer David T. Little. Its creation has been very moving for me. David wrote it for the ensemble Alarm Will Sound, which is conducted by my best friend, Alan Pierson, and which includes several members whom I’ve known, as I’ve known Alan, since my undergraduate days at the Eastman School of Music. (Keep an eye out for a conversation with Alan about Julius Eastman, coming soon.) It’s an opera for one singer (though the ensemble sings, too), who plays the narrator, and that part has been written for the exquisite tenor Karim Sulayman. Karim and I were students in the same voice studio at Eastman, studying with the tenor John Maloy. In 2019, Karim won the Grammy for Best Classical Vocal Solo for his wonderful album, Songs of Orpheus.

Anyway, the opera has felt, in the best way, like making art with my friends. But it’s about to go out into the world: performances are scheduled for fall 2024 (also when my new novel will be out, so a busy time). I’ll have much more to say about that in future posts; for now, here’s a short video about the project that Alarm Will Sound just released, where you can hear a bit of the music and learn about the collaboration.

*

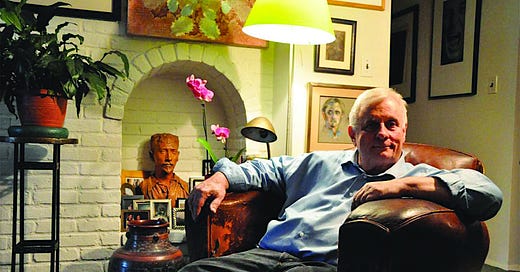

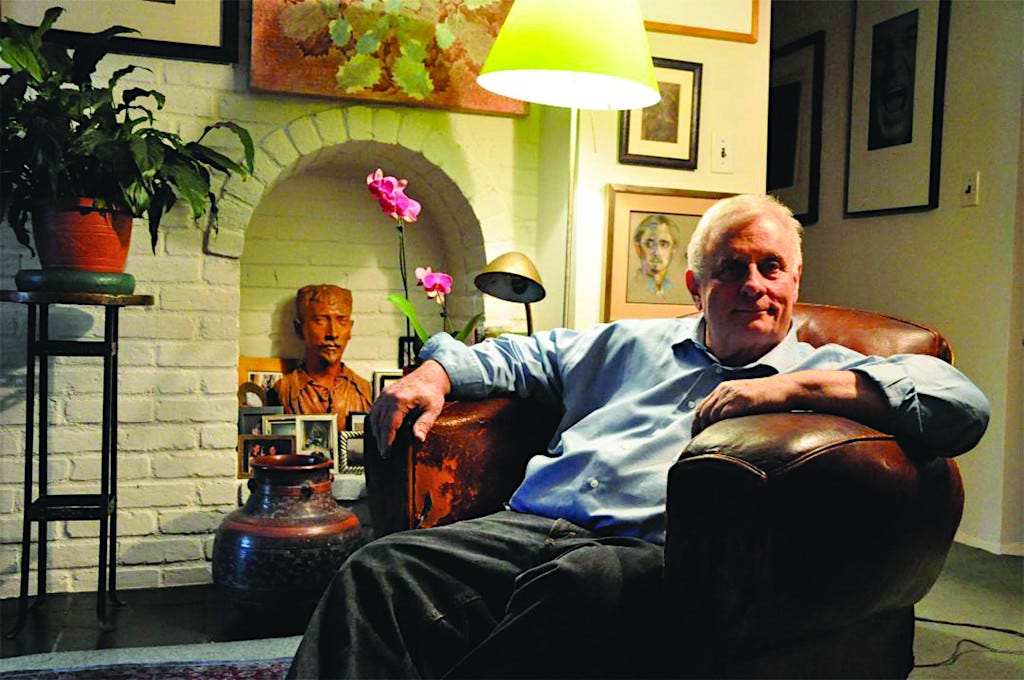

I’m very grateful to Edmund White for his generosity in chatting with me. Edmund is the iconic author of dozens of books, including an autobiographical trilogy—A Boy’s Own Story, The Beautiful Room Is Empty, and The Farewell Symphony—that is one of the crucial monuments of queer fiction. I’ve mentioned before that getting to know him better has been one of the best things about my move to New York. Edmund runs a kind of de facto salon in the Chelsea apartment he shares with his husband, the writer Michael Carroll; writers and artists of all stripes gather there to be regaled by Edmund’s impossibly erudite, endlessly charming, occasionally savage, always very funny conversation.

Earlier this year, Edmund invited the novelist Christopher Bollen and me to join him in reading pages of new work. I had just finished the draft of my new novel, and I chose the passage I read for two reasons: I had been typing it up from my notebooks that morning; and, as I had first written it, I had thought of Edmund’s most recent books for—well, not inspiration so much as courage. It’s a passage where the narrator, who’s in the hospital on bed rest and being bathed by his nurse, considers his own body. It was very hard to write.

Edmund’s work has always been radically candid in its writing of sex and the body. In his most recent books he has written movingly, shockingly, searingly about aged bodies. In A Previous Life, two lovers in 2050 read written accounts of their sexual pasts to each other—their sexual confessions. One of them is Ruggero, a now elderly Sicilian man, and the most important relationship he recounts is an affair he had decades earlier with the 80-year-old writer Edmund White. As Edmund describes below, this is based on the relationship—both “miraculous” and “horrible”—he had with a much younger Italian man named Giuseppe. Edmund’s most recent novel, The Humble Lover, is also a story of an age-discordant relationship, this time between Aldwych, an elderly, bumbling millionaire, and August, a dancer with the New York City Ballet. I read A Previous Life as a tragic book; The Humble Lover is a farce.

We talk about form, style, Elizabeth Bowen, the importance of bad taste, and the relationship between candor and humiliation. This is an edited and condensed version of a much longer conversation, but I’ve tried to leave in some of Edmund’s brilliant digressiveness, the way he’s constantly finding analogues in the cultural past. We started off by talking about what Edmund is working on now—a sex memoir, he said, which he’s having fun writing. But he also said that he was taking a bit of a break: that he was “on strike” because he’s disappointed by how little attention The Humble Lover has received from reviewers. Maybe this was because A Previous Life came out just last year and was widely reviewed, he mused. Or maybe reviewers just don’t want to read books about old people.

Edmund White:

And then my third theory is that everybody was taken up with Pride Month and all that. But this book is hardly a pride book.

Garth Greenwell:

Which is what I think is interesting about it.

EW

Me too.

GG

Neither of these books is a Pride book—and they’re better for it, I think. I’m fascinated by the form of A Previous Life. It’s a really strange book, and daring in the way that it dispenses with a lot of narrative stitching and much of the architecture we associate with novels. It sets up this situation between two characters, Ruggero and Constance—Ruggero has broken his leg, and to keep him entertained as he convalesces, he and his much younger wife, Constance, write their erotic confessions. That situation allows them to have these sort of dueling monologues. Those monologues are often very novelistic, very richly elaborated, but then you switch between them very swiftly and economically, often just by a section break and then a tag: “Constance” or “Ruggero.” It’s a very bare narrative structure, free of stitching.

EW

By stitching do you mean description? I don’t like description too much—I mean, unless it’s Elizabeth Bowen doing it. So many people just pile in page after page of rather dull description.

GG

This conversation isn’t an occasion for you to attack me, Edmund!

EW

Well, not you.