Writing Sex: What Comes After Rapture?

Some thoughts from Baldwin, Lawrence, and me; a perfect poem by Jane Kenyon; a new class

Two quick notes:

The Shipman Agency has announced a new quarter of classes, and I’m offering a four-week seminar on James Baldwin’s third and maybe greatest novel, Another Country, in April. I’m interested in thinking about ambition—how, after the contained, nearly perfect Giovanni’s Room (basically a two-hander, with a single POV), Baldwin sacrificed perfection in favor of a much larger canvas, and of a blazingly urgent attempt to write the agony of racism in America, especially that agony as lived by people trying very hard to love one another. It’s a brilliant, overwhelmingly powerful, imperfect novel, and I’m very much looking forward to taking our time with it. What a luxury: we’ll spend a whole class on the first 85 pages, an extraordinary sequence that may be the best thing Baldwin ever accomplished in fiction. Sessions will be recorded, and limited scholarships are available (on a rolling basis, so apply early). I’d love to have you join us.

Back in July of last year, Jamel Brinkley published a story in the Boston Review that absolutely knocked me flat. It’s called “Bartow Station,” and it’s collected in his marvelous second book, Witness. As I read and re-read it, I realized I needed to write an essay to try to explore what makes it so powerful. That essay is in the new issue of Sewanee Review, and they’ve made it their online feature, meaning it’s available to read for free. I’m grateful to the Review and its editor, Adam Ross, for letting me close read a single story at essay length. Talk about luxury! I write about Brinkley’s interweaving of past and present in his stories, his use of sex, his withholding narrators, his brilliant manipulations of style. I hope you’ll read it—both the story and the essay.

*

I’m teaching my Writing Sex seminar at NYU again this semester, though the syllabus is largely revamped: only three of the ten books overlap. I made the changes for a variety of reasons, including my own familiarity with some of the novels that were on the syllabus: I decided to remove books that I’ve taught three or more times (like Alexander Chee’s great Edinburgh, Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room, my beloved Pedro Lemebel, and Sabbath’s Theater). I realized that a few of the books last semester, while sexy, actually didn’t have much sex writing in them. It’s funny how you can misremember books. I remember Jeanette Winterson’s Written on the Body as being full of sex, for instance, but actually there’s very little. (It’s fascinating to teach for other things, though.) I have kept Colette’s The Vagabond, which has no sex in it, except that sex is displaced onto other things: nature, the act of writing, the sensuality of lonesomeness. It also has hands down the best description of a kiss I have ever read, which includes the single most ravishing line I know: “Je laisse l’homme qui m’a réveillée boire au fruit qu’il presse.” Unfortunately it seems to be untranslatable into English in any form that maintains its ravishment.

I also wanted more wildness on the syllabus. Last semester, only Yoko Ogawa’s great Hotel Iris (one of the books I’ve carried over) and Sabbath’s Theater really explored wild territories of erotic experience; this semester I’ve added J.G. Ballard’s Crash and Alissa Nutting’s Tampa. Have you read Tampa? I think it’s amazing—I read it again over winter break, to be sure I wanted to teach it, and it was as good as I remembered. It’s about a young woman who becomes a middle school teacher with the aim of seducing her male eighth graders. It’s a response to Lolita, a book I’m not teaching; Nutting adds madcap hijinks, and her heroine’s (is that the word?) psychopathy is glassy where Humbert’s is soupily literary. Never has a book made me feel more horrified of my impulse to laugh. I think that’s an accomplishment.

I also wanted more stylistic wildness, and to that end I’ve added Eimear McBride’s great The Lesser Bohemians, much of which is written in the style McBride calls “stream of existence”: a fragmented, radically imagistic, phenomenological prose in which bodily sensation is incorporated into consciousness. I haven’t read it in a couple of years, and have never taught it before; I’m excited to see what the students and I make of it together. I’m also excited to teach for the first time Giuseppe Caputo’s An Orphan World, maybe the most interesting literary exploration I’ve seen (along with Dennis Cooper’s The Sluts) of online sexuality. Caputo interweaves scenes of Chat Roulette-type video cruising with real-world, analogue cruising, to fascinating effect. It’s a book I’ve been wanting to return to for a long time. The last book on the syllabus is also a novel of online intimacy, Barbara Browning’s The Gift, which (like Colette) will challenge our ideas of what sex writing can look like. (I did an episode of the Public Books podcast about the book with the scholars Daniel Wright and current National Book Critics Circle finalist Nicholas Dames back in 2021; I remember it being a lot of fun.)

Anyway, if you’re interested you can find the whole book list here.

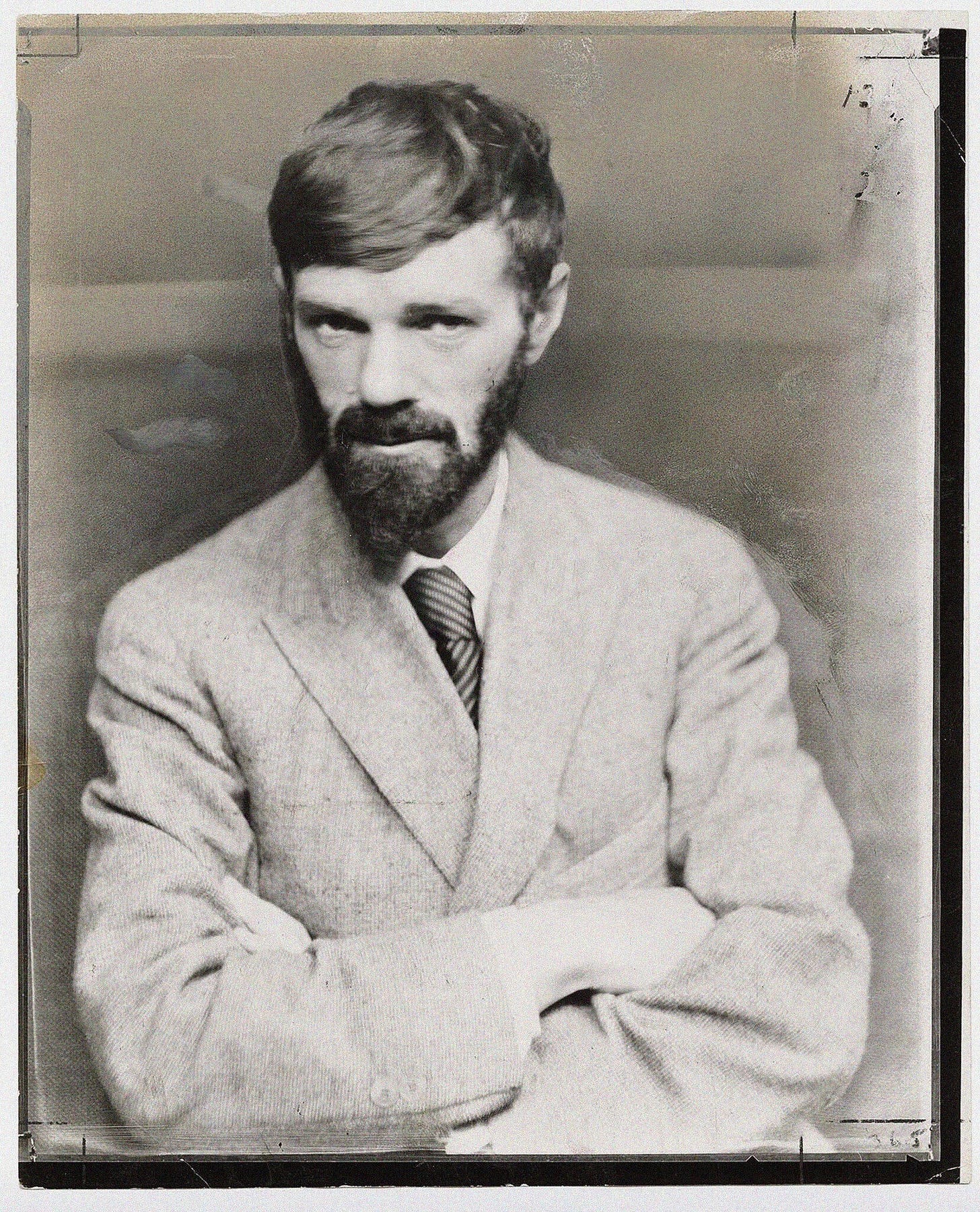

We started the semester with another holdover, D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. I find the book more fascinating, and also more frustrating, every time I read it. Frustrating for its wacky, occasionally sinister politics and theories of life, but also frustrating as a novel: formally confused, thematically incoherent, full of false starts. To be honest it’s a mess, and maybe one of the prime examples of a vanishingly rare category: bad novels that are also great. What makes it great? The writing, for one thing, which is astonishingly great at times, I think more often than it’s astonishingly bad. The nature writing is impossibly good. Listen to this: “The sheep coughed in the rough sere grass of the park, where frost lay bluish in the sockets of the tufts.” Anyone who can write a sentence like that has as much of my attention as they want. I admire the book’s courage in smashing through expectation and convention, especially in imagining a woman’s desire—and in representing a male body as object of that desire.

The book’s sex writing is sometimes as bad as the rest of the writing can be; sometimes it’s astounding; sometimes it’s both at once. I love starting the class with it because there’s so much sex in the book, and of such varied kinds. (Another topic for another Substack: straight men, to the extent Lawrence was a straight man, writing anal sex.) Probably the most famous passage in the book is one in which Lawrence marshals extraordinary linguistic resources to describe female sexual experience, introducing a new texture to English-language prose: