I remember my first glimpse of him. This was in 2015, and in my memory it’s one of New York’s brilliant spring afternoons, though I’ve learned not to trust my memory in these things. I think I had just finished a mid-life graduate program and was in the city for a visit; a friend and I were making the New York rounds, seeing friends and writers. I was in that vibratory state of just-contained panic that precedes book publication: my first novel would come out a few months later. Edmund was on my mind: several weeks before, in an act of generosity he extended to hundreds of writers over decades, he had sent my editor a blurb. My friend and I had made plans with Edmund’s husband, the writer Michael Carroll (whose very beautiful book of stories, Little Reef, I had reviewed for the gay blog Towleroad), to meet later that afternoon at their Chelsea apartment, where I would finally have a chance to thank Ed in person. I’ve just looked again at my editor’s email sending me Edmund’s comment, the first we received for the novel; its subject line reads, “A very good day.” It was.

And then: there he was, in the spring sunshine, making his way down the other side of the street with a cane. What street was it? Again my memory sets the stage too well for credibility, but it puts us somewhere in the asterisk of streets around Christopher Park and its Segal statues: the heart of gay New York, of the gay universe; a neighborhood that, even though now I spend half the year teaching just a few blocks away, still seems mythical to me, an inner region of the realms of gold. In any event, that would be the only time I saw Edmund walking in the street, almost the only time I saw him anywhere but his home. (I went to his events when I could, especially when they were at Albertine, my favorite NYC bookstore; and once a very handsome Australian man and I took him to a Thai restaurant that had been written up in the Times.) I remember him dapper in a blazer, maybe even a tie. I remember thinking that he looked like a dream of Edmund White.

I had been dreaming of him for a long time. There’s no gay writer whose career Edmund hasn’t influenced, even if they don’t know it: he made all of us possible. I read his work for the first time when I was sixteen, newly arrived at the Interlochen Arts Academy in Michigan; I found it in the old fashioned way, by searching the card catalog. That was one of the first things I did when I got to Interlochen, a rite of passage that hadn’t been possible in my public high school in Kentucky: flipping through the cards until the subject headings began “Gay--Fiction” and then reading through the books one by one. Like most people, I started with A Boy’s Own Story, Edmund’s great novel from 1982. I read it avidly, not least because much of it takes place in Cincinnati, not far at all geographically from where I grew up. (Culturally it was a different world: Cincinnati is incontestably (to us, anyway) Midwest; Louisville is the South.) Kentuckians fill some of the novel’s stickiest, funniest, saddest pages: farm boys who cross the river to make a little money in exchange for sex, including money from the novel’s adolescent protagonist.

I had already read Giovanni’s Room by that point, but here was gay life happening not in glamorous Paris but dowdy Cincy; a radical thought. Still, another book of Edmund’s was even more important for me—a new book in 1994, which I think I found in a bookstore in Traverse City: The Burning Library, a collection of Edmund’s reporting and cultural criticism, a brilliant overview of the gay cultural scene. Impossible to say the impression that book made, with its profiles and reviews of Hervé Guibert, Marguerite Yourcenar, Darryl Pinckney, Michel Foucault; it gave me a kind of map to gay intellectuality, a field guide to the territory I would spend the next decades exploring. With the possible exception of Colm Tóibín’s Love in a Dark Time, which came out a several years later, I’m not sure any book had a more profound or lasting impact on me as someone who would, though I didn’t know it yet, eventually make my way as a writer.

So imagine what I felt as we crossed the street to introduce ourselves, as he stopped and acted like he had all the time in the world, like nothing could be so delightful as talking with us. I’m not sure I’ve ever met anyone so charming; and part of his charm was making you feel he was always happy to see you. I never saw Edmund be anything other than kind, to anybody; though it’s also true that he could be withering, devastating, in the things he said when somebody wasn’t around. The things he said behind their back, I guess you could say, though that sounds petty in a way Edmund never seemed, maybe more than anything else because of his style: gossip is a gay art, and Edmund was its master. (If his letters or diaries are ever published, I’m pretty sure we’ll all be toast.) In any event, he seemed perfectly happy to be accosted by two youngish gays in the street, and honestly probably he was—if only because my friend was glamorously beautiful, and Edmund had a weakness for beauty. But he was lovely to me too, and quickly he had us laughing to tears. I loved your novel, he said to me, in that voice that was fruity, expressive, still midwestern but tinged by Europe, steeped in another generation’s gayness. How do you write so lyrically, he asked; and then, with perfect earnestness, he really wanted to know: Do you only write when you’re a little drunk?

Praise with an undertow; I fell in love. I had always loved Edmund White, for the example of his work and his life, for who he was in his books; but I loved him, too, the Edmund I met that day in the street and would get to know over the next decade. I did love him, though I didn’t ever get to know him all that well, really; I wasn’t one of his intimates, or part of the coterie various members of which I ran into almost every time I visited his apartment. How many times was that? A dozen? Fifteen? I remember how I felt that first time, walking into the living room where Edmund and Michael entertained, which was like a habitable consciousness, overflowing with books, including Edmund’s books, in various languages; but also brimming with art, paintings and photographs, even a bust or two, many of them featuring Edmund himself. (A Mapplethorpe photograph in the corridor leading to the bathroom always made me catch my breath.) Frank Bidart used to say that his dream was to have an apartment so packed with art that all of Western culture might be reconstituted from it; Edmund wasn’t anything like the hoarder Frank is, but his and Michael’s apartment gave something of that impression: maybe not all of Western culture, quite, but a good bit of it. Certainly the gay bits.

Not that you paid much attention to the apartment or its objets d’art, once Edmund started talking. Nobody talked like him; nobody was so erudite, so funny, so vulgar, so endearing; nobody had seen as much, lived as much, known as many people; nobody was so dear. He had all the best, the gayest virtues, gliding among centuries, languages, worlds; he could talk about the memoirs of an obscure 17th-century French courtesan at one moment, a Handel aria the next, then hold up some fan’s nude selfie that had just landed in his phone with a ping. Impossible to keep up; you could only give yourself over. He always knew more than you did, about everything, but he never made you feel small. He tossed out compliments like spare change. He was like you, he said to me once, talking about an old friend, he had read everything—which made me bark with laughter, one of the few times I interrupted him. But Edmund, I said, I haven’t read anything, which was how I felt, always, in his company; I haven’t read anywhere near as much as you. Oh, but you will, he returned. By the time you’re my age…—and he trailed off, as if the possibilities were endless. Maybe that was the key to his charm, or to his legendary generosity: he could imagine the ideal version of yourself you might one day become.

I tried never to interrupt Edmund; I loved to hear him talk, I could listen to him for hours. (I realize this means I was a bad guest, making him do all the work of sociability; I hope he forgave me.) The life he had lived—enough life for three lives, for four. He had known everybody, most of them biblically. He was gay history, a living embodiment of it; his life mapped almost perfectly onto the modern gay movement. Everybody used to say they were at Stonewall; Edmund actually was, an event he would narrate repeatedly in his novels and memoirs. He was in his prime in that unprecedented world of gay sexual sociality that flourished in the 1970s, and in fact was one of its architects, as co-author of the revelatory, revolutionary The Joy of Gay Sex. Edmund counted himself among the first (in the late 70s, he thought) infected by the virus that would dismantle that world; he became one of the great chroniclers of the devastation AIDS would wreak. He lived long enough to pass through every possible stage of a writer’s career: early fame, periods of acclaim and neglect, a late flowering of deserved recognition. He was old enough, by the time our new-old, reactionary moralism took hold, that age protected him from the worst of it; he used to say that he retired from Princeton just in time. It’s not hard to imagine the alternating waves of liberatory amazement and scandalized shock that his work will continue to provoke.

Once in an interview I read long before I started publishing books, Edmund complained that after he blurbed young writers he never heard from them again. I hope he didn’t feel that in my case; I hope I made clear how much his work meant and continues to mean to me. A couple of years ago I was asked to write an introduction to his second novel, Nocturnes for the King of Naples, which gave me an excuse to reread many of his books. A Boy’s Own Story more than holds up, almost forty-five years later; it’s still a very good place to start if you’re new to Edmund’s work. In that introduction I make my case for Nocturnes as the best of Edmund’s early experimental books, an exquisite stylistic performance. But my favorite of his novels is Hôtel de Dream, a short, gem-like fantasia on the life of Stephen Crane. I also love his collection of short stories, Skinned Alive, which has pages live as electric wires. The Farewell Symphony, the third of his trilogy of autobiographical novels, is frequently cited in surveys of important AIDS literature; I find The Married Man, with its utterly lacerating final sequence, even more powerful. His late novels make important contributions to the writing of sex; they’re almost unique in their writing of aged, infirm, still-desiring bodies. (I interviewed White about this in November 2023.) Which isn’t even to touch his nonfiction: The Burning Library, the great biography of Genet, the many volumes of memoirs.

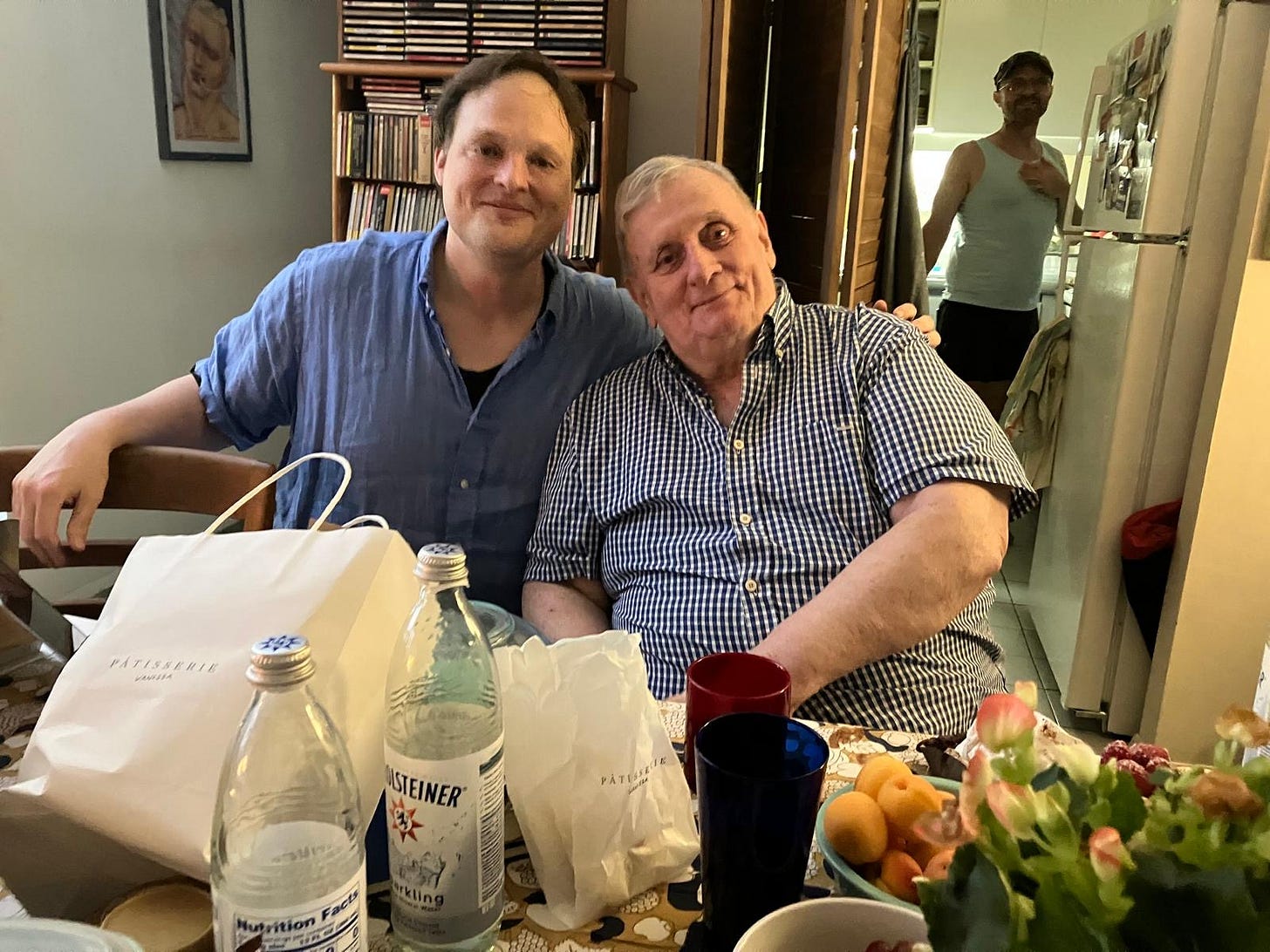

Somehow I had convinced myself that he would live forever. But human beings aren’t ever monuments, really, however iconic they come to seem. Wednesday morning, here in Madrid, I woke to the text from Michael telling us that Edmund had died. Luis was already up; I called him back to bed. A reliable joy for me in recent years was how much Luis and Edmund loved each other; seeing them together was the only time I saw Edmund as charmed by someone as I was charmed by Edmund. How sad I am, how sad we are, that he’s gone. How much richer the world is for his having lived.

As always, thank you for reading—

G.

Only you could write something as graceful as this about him this quickly. Thank you for this loving remembrance that also acknowledges how rare he was and how. Sending you much love.

This must be the most beautifully written remembrance I've ever had the honor of reading, Garth. It exudes love and respect in a manner only you can achieve. Thank you for this.